Childhood

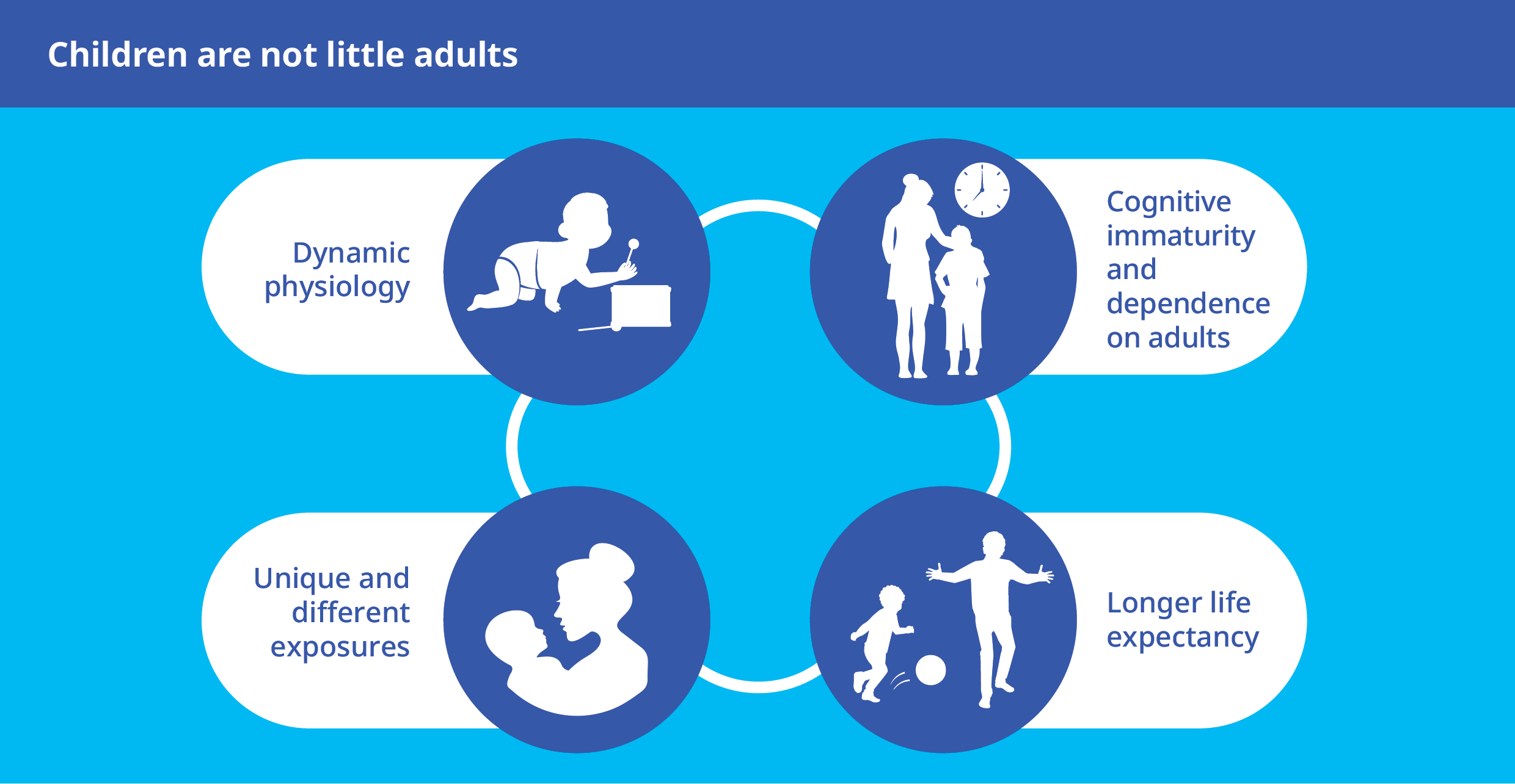

Environmental hazards affect infants and children in different ways than adolescents and adults due to dynamic physiology and metabolism, unique and different exposures, cognitive immaturity and longer life expectancy.

As soon as a newborn breathes for the first time, environmental hazards can begin to affect development due to the unique vulnerabilities of children. Children eat, drink and breathe relatively more than adults, meaning they also take in more harmful contaminants. In addition, they are less able to break down and expel toxicants. Children have more contact with environmental hazards. They are closer to the ground where toxicants like soil and dust settle. Their exploratory hand-to-mouth and object-to-mouth behaviours make them more likely to ingest harmful substances.

Children – especially infants – grow rapidly, making them more at risk of malnutrition, which can be increased by environmental hazards that cause food and water scarcity. Moreover, children’s limited diets can lead to greater exposure to food contaminants, like pesticides or microorganisms. Breast milk can pass harmful environmental exposures from mother to child. Infants and young children are more prone to dangerous heat loss as well as overheating. Even into later childhood, children are less able to adjust to rises in ambient temperature than adults.

Children's dynamic physiology makes them uniquely vulnerable

Children eat, drink and breathe more per kilogram of body weight relative to adults because they are growing. This difference is even greater in infants compared to older children. This can lead to higher rates of intake of harmful substances per kilogram of body weight when there are contaminants in food, water and air.

As children have different nutritional needs, the small intestine can respond by increasing the absorption of certain nutrients. For instance, calcium absorption in infants is around five times the rate of that in adults. Some environmental toxicants, such as lead, can compete with nutrients and also be absorbed at higher rates. The ratio of a newborn’s skin surface area to body weight is three times greater than that of adults, meaning their skin can absorb more of a harmful substance per unit of body weight than that of an adult.

Children’s ability to metabolize, or break down, harmful substances that enter the body changes with age. Take, for example, organophosphate pesticides, which can cause both acute poisonings and chronic low dose exposures and are known to affect cognitive development. The body has an enzyme called PON1 which detoxifies organophosphate pesticides. Measured activity of PON1 is lower in children up to at least 7 years of age, creating a period of increased vulnerability to these pesticides.

The body eliminates waste through the kidneys via urine, the gastrointestinal tract via faeces and the lungs via exhaled air. The kidneys are the main route of excretion. At birth, the filtration rate of the kidneys is about one third of adult values, increasing to adult levels by age 8–12 months. This means that infants clear substances excreted by the kidneys at a slower rate than adults.

In addition to having increased respiratory rates, there are structural and functional differences between the airways of infants and children compared to adults. Infants up to age 2–6 months breathe primarily through their nose which makes them more vulnerable to conditions which block their nasal passages, such as upper respiratory infections, which are associated with exposure to air pollution. The size and shape of the airway between the larynx and trachea is also different, which means that even small amounts of oedema can significantly reduce the diameter of the paediatric airway, decreasing airflow and making breathing more difficult.

Haemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen, is different in infants compared to adults. At birth, newborns have 65–90 per cent fetal haemoglobin, which is present in utero. Levels of fetal haemoglobin decrease by 6–12 months of age, when only 2 per cent of total haemoglobin is in the fetal form. The presence of fetal haemoglobin makes infants more susceptible to carbon monoxide poisoning, because fetal haemoglobin is more likely to bind with carbon monoxide than adult haemoglobin.

Infants and young children regulate temperature differently than adults which makes them more vulnerable to extreme temperatures, both low and high. Their ratio of body surface area to mass is greater than that of adults which permits greater heat transfer between their bodies and the environment. In addition, they have higher metabolic rates and heart rates, they spend more time outdoors and in vigorous activities, and they cannot remove themselves from environments with unsafe temperatures. Children under 1 year of age are especially vulnerable to heat-related deaths. Extreme temperatures are increasingly more likely due to global climate change.

Adaptive immunity is not present at birth but is developed over time. It involves specialized immune cells and antibodies that attack and destroy foreign invaders and are able to prevent future diseases by remembering what those substances look like and mounting a new immune response. A newborn’s adaptive immune system functions differently, making them more susceptible to respiratory infectious diseases and reducing their response to vaccination.

Although the blood-brain barrier is fully functional at birth, activity of transporters and enzymes at the barrier differs from adults to meet the needs of the developing brain. This means that movement of harmful substances can differ, making infants more vulnerable to chemicals. Some harmful substances, such as lead and cadmium, may cause oxidative stress leading to a weakening of the blood-brain barrier and allowing transmission of these substances into the brain.

Children’s unique vulnerabilities to environmental hazards

Environmental hazards affect infants and children in different ways than adolescents and adults due to dynamic physiology and metabolism, unique and different exposures, cognitive immaturity and longer life expectancy. This brief focuses on the specific effects of environmental hazards in infancy and throughout childhood. Health effects that emerge during childhood as a result of antenatal exposures are not reviewed.