Pregnancy

Every child has the right to a healthy start in life. But environmental hazards can cause harm before a child is born or even conceived. Environmental hazards can damage the egg or sperm cells long before conception takes place, and the effects can be passed down from generation to generation. The fetal period is critical as it shapes a child’s lifelong health and development.

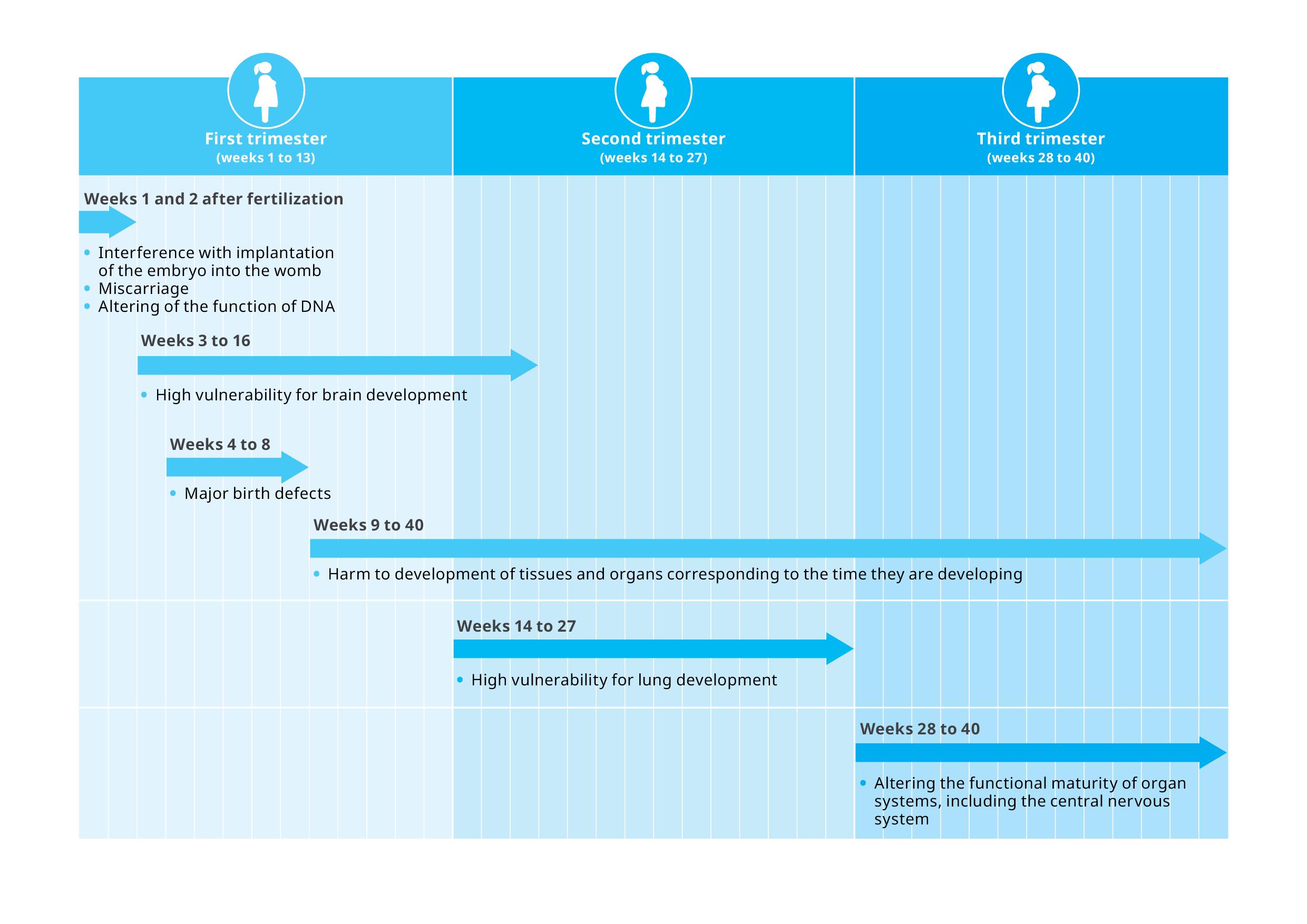

There are critical windows of vulnerability to environmental hazards, particularly during the first trimester, when women might not be aware of their pregnancies. Adverse birth outcomes such as miscarriages, stillbirth, preterm births, birth defects and low birthweight have been linked to exposure to environmental hazards. A fetus’s developing cells, organs and tissues are uniquely vulnerable to damage from environmental hazards. The consequences can last a lifetime, including health conditions like obesity, cognitive impairment, neurological disorders, lung disease and cancer which can arise in infancy into late adulthood.

While all women are at risk, the heaviest burden falls upon women in low- and middle-income countries, especially those living in fragile and conflict-affected situations, deepening inequities between groups. Preventing exposure to environmental hazards can ensure that future generations live to their full potential. It can also prevent economic loss to countries, including to health systems.

Pregnant women and the developing fetuses' are uniquely vulnerable

A pregnant woman needs more food and fluids than a non-pregnant woman. This increases a pregnant woman’s exposure to toxicants in contaminated food and drinking water. An increased need for fluids during pregnancy also puts a woman at risk of dehydration. This can cause low amniotic fluid levels, which limits fetal movement and creates pressure on the fetus from the umbilical cord. Diseases like cholera, which make people lose fluids, make pregnant women especially susceptible to dehydration. Severe dehydration can compromise blood flow to the placenta and cause harmful levels of acid in the amniotic fluid, leading to fetal death.

Hormonal changes during pregnancy drive key changes in a pregnant woman’s respiratory system, which can affect the body’s response to environmental hazards such as air pollution. Pregnant women inhale more air per minute, which means they will breathe in more air pollutants. Air pollutants can have a duel negative effect because they can both harm the fetus directly and act systemically by creating inflammation and reactive oxygen species, which are unstable molecules that can damage DNA.

The movement of substances, including chemicals, in a body can change during pregnancy. For example, a pregnant woman’s bones will remodel to release calcium for the fetus, which can release lead into the bloodstream at the same time. Other changes include the movement of fats in the body. Early in pregnancy, the storage of fat increases in a woman’s body. Later in pregnancy, fat is broken down to provide energy for the fetus. ‘Fat-loving’ (i.e., lipophilic) toxicants can be stored in this fat and then released into a woman’s bloodstream, which can potentially reach the fetus. Lipophilic chemicals include an array of harmful persistent pollutants, such as DDT, dioxins and heavy metals.

Other metabolic shifts to support fetal growth and development include changes in the metabolism of glucose and proteins. These changes are hormonally controlled and susceptible to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) and other toxicants. When metabolism during pregnancy is negatively affected by EDCs, diseases such as gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders or restricted fetal growth can occur. Miscarriage can also happen.

During pregnancy, the heart increases the amount of blood it pumps per minute. The total volume of blood, including the plasma (i.e., the liquid portion of blood) is also increased. Increased plasma volume is critical to maintain blood flow to the uterus. Low plasma volume is associated with gestational hypertension and other pregnancy complications. Red blood cell production also increases in pregnancy. As iron is a key component of these cells, pregnant women require more iron. Conditions such as food insecurity, which may reduce availability of iron from dietary sources, can lead to iron deficiency and anaemia.

Changes in heat regulation to cope with the metabolic changes related to pregnancy include increased blood volume, dilation of blood vessels in the skin and increased sweating.45 If a pregnant woman is exposed to extreme heat, she may not be able to transfer enough heat to the external environment. If this happens, her health and the fetus’s health can be affected, with consequences for newborn and child health if the pregnancy goes to term. Extreme heat experienced during pregnancy is associated with preterm birth and has been linked to gestational diabetes, low birthweight and congenital anomalies.

During pregnancy, a woman’s immune system will effectively suppress itself to enable the fetus to grow. This increases a woman’s susceptibility to certain infectious diseases and the severity of illness. It also increases the risk of fetal death. Research shows that pregnant women have an increased incidence of many types of infections, including some mosquito-borne illnesses that are increasing due to climate change, such as Zika virus infection and malaria.

Timeline of health impacts from exposure to environmental hazards by trimesters

Pregnant women and the developing fetuses’ unique vulnerabilities to environmental hazards

During preconception, conception and all the months of pregnancy, there are critical windows of time where certain cells, organs and tissues are most susceptible to environmental hazards. Understanding these windows can shed light on why environmental hazards can devastate a pregnancy or cause effects on health and development decades later. Protecting pregnant women from environmental hazards is an important step to ensure the health of future generations.